miChelle M. Vara

6 Ballard Road, Wilton NY 12831, USA

Email: michellevara09@gmail.com Web: https://www.michellevara.com

Ph: 518-744-1664

The Process of Creative Force

I spent a half of a lifetime avoiding writing and school. The stress and pressure of not being good enough because of a disability has crippled me for a decade. I have always loved to learn and spent 20 years learning to really read, and then I read philosophy looking for perspectives too glean and apply to my thoughts and work. I realized way back that everything seems to stem from philosophy. Humans always want to know the how and why of the patterns of thoughts and actions of other humans. This year I took on Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO), which took me down a road of confusion and dissolution. How could I go wrong with three o’s—after all, Gram Harman was talking about the metaphysics of objects, and I believe objects hold memory and spirit. I read it all, starting with Tool Being, Guerrilla Metaphysics, The Quadruple Object. I kept insisting I must be missing something, so deeper I went. Lectures, articles, YouTube. I kept thinking, I know there’s a common denominator I must be missing—after all, his work is titled Metaphysics of Objects. I was literally driving myself crazy until my advisors simply said things like “That’s a slippery slope you’re trying to climb” (Chris Danowski—I Skyped him multiple times on the subject and he gently kept saying run in the other direction) or “You know, there’s a lot of artists whose writing might better be applied” (Michael Bowdidge). Yes—constructive criticism to the rescue.

So off to the playground where I like reading, and to limber up I went back to an old favorite artist, David Smith. Since I struggled in philosophy like a fish out of water, I thought, Why don’t I treat myself to a new book? With that I bought to date my favorite out of my collection: David Smith: Documentary Monographs in Modern Art. This book offers Smith’s words and lectures, allowing the reader to really connect to the person he was. The other book that I think offers great depth and insight is Lois Orswell’s David Smith and Modern Art.

I have spent years believing that the creative process in a completed visual work needed no words to communicate. David Smith said the same types of things, but all the time writing, giving lectures, and chatting it up while smoking cigars and drinking with the heavy hitters of his time in the art world. He belonged to the New York Painters. Wikipedia says he was best known for his abstract geometric sculptures, which I disagree with. To me he is the father of the welded found object sculpture, where he captures the essence of spirit from within the object and connects a higher personal calling with mechanical techniques for aesthetically pleasing visual dialog. Smith said in an interview with David Sylvester, “I have seen that man works better when he is working within his own spirit. We are working to extend our own potential” (Sylvester, 1964). I thought to myself, Spirit, potential, and perception are all catchphrases of the pyramidal thinking of hoi polloi. That brings me to the idea of conviction David Smith wrote in a speech given at the Eighteenth Conference of the National Committee on Art Education at the Museum of Modern Art, New York: “The work that’s produced depends much more on the conviction of the man who produces it. You work from your identity—that demand from yourself—by personal conviction of your own cause, more than fads or order of your time” (Smith & McCoy, 1973). It seems to me the convictions instilled from childhood in your person follow you as a lifetime of practice or habits. Smith goes on to say, “You must first teach people to use their own sense, I do not know how you teach roots, courage, visual thinking, perception. Developed by work and work discipline. Upbringing one cannot argue creative force comes through you as if possessed over coming all opposing will.” Although the first half of my life I connected to a visual dialog that was laid out for the viewer, this is where I began to really connect to his words, and in agreement I think higher forces drive a human like me to the insatiable creation mode. As a child of a parent who was everything but traditional, we worked all the time; life was fast, always thinking in motion.

Belief is just a thought you keep thinking (Hicks & Hicks, 2009) unless it is forgotten and runs in the background as preconscious thought. The preconscious contains thoughts and feelings that a person is not currently aware of but that can easily be brought to consciousness (Freud, 1924). It exists just below the level of consciousness, before the unconscious mind. The preconscious is like a mental waiting room, in which thoughts remain until they “succeed in attracting the eye of the conscious” (Freud, 1924, p. 306). Finally, the unconscious mind comprises mental processes that are inaccessible to consciousness but that influence judgments, emotions, or behavior (Wilson, 2002). According to Freud, the unconscious mind is the primary source of behavior. Like an iceberg, the most important part of the mind is the part you cannot see. Our feelings, intentions, and decisions are actually powerfully influenced by our past experiences and stored in the unconscious. Freud applied these three systems to his structure of the personality, or psyche: the id, ego, and superego. Here the id is considered entirely unconscious, while the ego and superego have a conscious, preconscious, and unconscious aspect (McLeod, 2009). All this has a direct influence on completed creative works and where I question connection to god, self, or automatism. I find grace stored in meditation, which brings honesty with one’s self.

Smith said he asked for advice from Motherwell on the speech he was to present because Motherwell had been staff at Hunter College. The speech was given at the Eighteenth Conference of the National Committee on Art Education in 1960, called “Memories to Myself.” Motherwell said “be honest,” and as I felt with this paper, Smith said, “I’m not sure what to say.” One of his most exposing ideas conveyed in that speech is “I think the freedom of gesture and courage to act are more important than trying to make design” (Smith, 1968). Smith’s actions were tireless, and I think in his case as in my own it’s not work—it’s the path of existence. He talks of teaching perception as an opening into vision that exists nowhere else but in education. I ask, How do you teach perception? You can be exposed to experience and you can read, but perception is an individual take, cumulative of multiple factors. But definition explains: the ability to see, hear, or become aware of something through the senses. Good, bad, or indifferent is similar to opinion. An opinion is a view or judgment formed about something, not necessarily based on fact or knowledge. So I’m left thinking education is exposure to fact—through fact one can gain opinion and perception. Of course, there’s a doctrine of thought not documented here but that could lead to volumes of dialog if we are to look at it through glasses of psychological theory. Then there’s fact, and among the spiritualists it is said fact relies on who is telling it and what point of view or camp they are from.

Smith said, “Drawing is the most direct, closest to true self, most natural liberation of man. Each must dig himself out of his own mind and liberate the act of drawing to the vision of memory.” I find once it is drawn in a sketch book, it is released, until the time it has been chosen for another task. The revisit or looking in on the drawing ignites the memories of time, event, or even place, causing a flood back as if not a moment had passed. The drawing’s currency is fluent. The same happens with photography for me. “Photography, as a powerful medium of expression and communications, offers an infinite variety of perception, interpretation, and execution”; “No man has the right to dictate what other men should perceive, create, or produce, but all should be encouraged to reveal themselves, their perceptions and emotions, and to build confidence in the creative spirit” (Ansel Adams). Again, personal perception is a vital component in the creative mix. Revealing oneself in the world through art is a brave, complicated, and tenacious act. This statement has been said in many ways by many well-known artists throughout time, and I truly agree. As personal reflection goes, I have asked myself on different occasions and in different places: Why? There are so many easier ways than confronting issues and ideas always being different and choosing extremes, working harder than a draft horse owned by an Amish family and saying more with no words, contemplating realities, seeing things unseen, sprawling inside-out for all or anyone to judge. As an artist, you lay out a smorgasbord to have a viewer stop by a gallery and say, “So you’re doodling now” as they slip into their million-dollar life where airplanes, cocktails, and warm beaches wait.

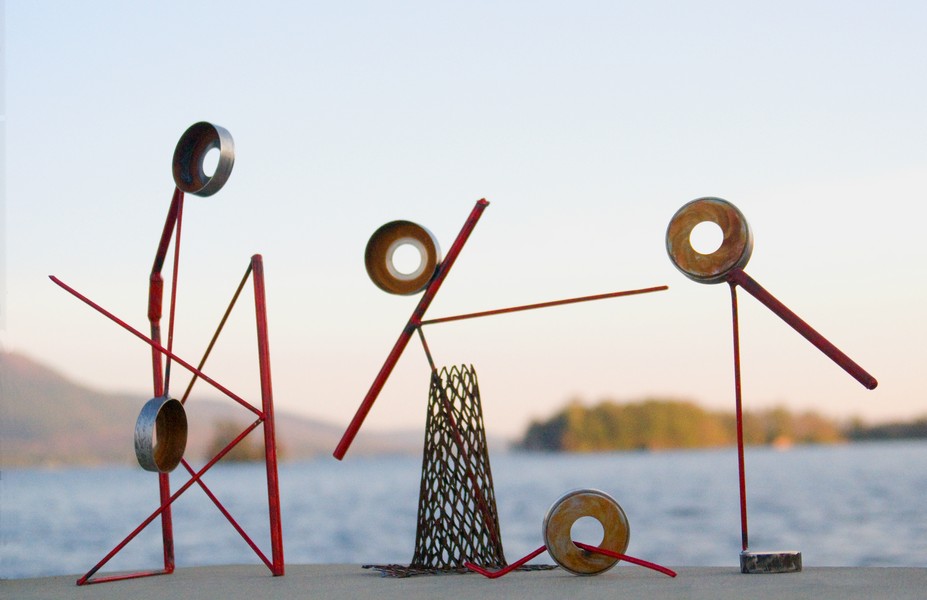

This all alludes to the process of creation in a dig and dance between physical and mental, balancing conscious and unconscious, drawing lines in space to be bound in like manners of welding. The practice of connecting metal together plays to fuse emotion, spirit, and material, creating context by placement in permanence, by heating and adding rod or filler metal for objects to be formulated. Questions bounce like the flicker and strike of a welding arch. Do I formulate the object, or does the object formulate me? The smell of burning metal creates context to the human experience as muscles grown in physical labor, sweating with the pounding of hammer against steel to form shape, psyche drilled with holes of past, present, and future, clamping experiences into contexts. Safety glasses fog with multiple perceptions while caressing statements from the hardened steel like a lover who has grown comfortable. The grinding of metal canters emotion into small shards forming finish and outcome. The welded sculpture process is dirty, physical, noisy labor that offers a beautiful rhythm overcoming the world’s demanding chatter, allowing space like the vortex, communicating beyond physical reach into a meditative dimension. The object of art contains all honest identity and beyond. The finished piece is free to do its will like a child coming of age. Physical ease to no labor’s end, clean the studio like emptying the mind of the last relationship. In exhaustion the world wants posts, blogs, words, a name, so comb a dictionary, mindfully plotting each word, description, or thought. To start again tomorrow.

References

Freud, S. (1924). A general introduction to psychoanalysis. New York, NY: Pocket Books.

Hicks, E., & Hicks, J. (2009). The vortex: Where the law of attraction assembles all cooperative relationships. Carlsbad, CA: Hay House.

McLeod, S. (2009). Unconscious mind. Retrieved from http://www.simplypsychology.org/unconscious-mind.html

Smith, D., & McCoy, G. (Ed.). (1973). David Smith (Documentary monographs in modern art). London, England: Allen Lane.

Smith, D. (1968). Memories to myself. Archives of American Art Journal 8(2), 11–16.

Sylvester, D. (1964). Interview with David Smith. Living Arts.

Wilson, T. D. (2002). Strangers to ourselves. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

We are the importance of today as tomorrow never comes.

Seize the day!